How to cover the growing costs in athlete compensation? Here comes a fresh idea: A loser’s tax on coaches, from Mike Gundy to Mike Norvell.

Once a runaway train, coaches’ salaries go under microscope as colleges brace for revenue-sharing with athletes.

LSU’s Brian Kelly says he must ‘put my money where my mouth’ is and contribute his own dollars to help bankroll the operation.

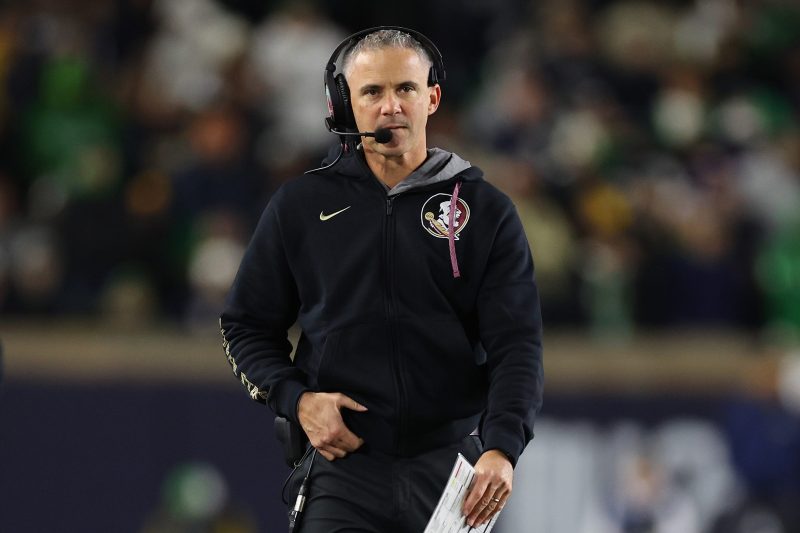

At Florida State, they’re calling the fundraising campaign a Vision of Excellence, but coach Mike Norvell’s $4.5 million contribution to the initiative comes off as a penalty for putridness.

The college sports pay-for-play revolution entered new terrain this month. Norvell became the third known coach who underperformed this season and now will help bankroll the operation.

It started with Oklahoma State’s Mike Gundy agreeing to reduced compensation to retain his job after the Cowboys flopped their way to a 3-9 record. The cost savings will be redistributed through the school to athletes, according to multiple reports.

Next, LSU’s Brian Kelly announced a campaign to match fans’ donations to the Tigers’ NIL collective, up to $1 million. Kelly failed to make the College Football Playoff in his first three seasons at LSU while ranking among the nation’s top-paid coaches. NCAA rules prohibit coaches from making direct NIL donations, but Kelly will use a workaround by funneling his donation through the Tiger Athletic Foundation, a booster group that financially supports LSU athletics.

So, yeah, same effect.

“I needed to put my money where my mouth was and be a part of (funding a championship roster),” Kelly said.

Used to be, a coach bankrolling his roster amounted to a major NCAA rules violation. Now, a coach can declare his payments on the up and up as part of a fundraising campaign.

The optics are a bit odd, although not entirely unexpected.

It’s more evidence of scales of power and wealth shifting within a landscape in which athletes are compensated.

NEW BOSSES: Where does Bill Belichick rank among the coaching hires?

Mike Norvell, Mike Gundy pony up after losing seasons

Since 2021, athletes can collect third-party deals to profit off their fame and abilities. Donors, businesses and fans foot this NIL bill. Schools were spared from paying athletes – but not for much longer.

If a legal settlement gains final judicial approval in April, schools will begin coughing up millions annually for athletes via revenue-sharing. Although revenue-sharing won’t be required, any school wishing to compete at the highest level will feel compelled to opt into a plan that permits schools to redirect more than $20 million annually in athletics revenue to players.

How to cover these new costs?

Here comes this fresh idea: A loser’s tax on coaches.

“I presented this to our administration in an effort to boost the support of our student-athletes,” Norvell said Monday in a university release announcing his payment to Vision for Excellence as part of a restructured contract, “while recognizing that the results and expectations need to be upheld to the highest level.

‘I wanted to be proactive in my financial assistance through this time of transition as we all push forward to get back to the standard of Florida State football.”

Norvell won 13 games in 2023 and earned a raise. With a $10 million salary, he ranked among the nation’s top-paid coaches. That equated to $5 million per victory this season.

Pay-for-play revolution puts new scrutiny on coaches’ salaries

Before NCAA rules permitted player compensation, athletics revenue had to go somewhere. Some of it funded Olympic sports, while other dollars poured into facilities upgrades that would make professional organizations blush. Also, coaching salaries ballooned. Some mediocre coaches now earn salaries topping $7 million, while championship coaches like Georgia’s Kirby Smart ($13.3 million) and Clemson’s Dabo Swinney ($11.1 million) earn eight figures.

Some schools already have shown more caution toward facilities projects, wanting to preserve precious dollars for players. Now, we’re seeing cases of money being clawed back from a few coaches.

Nothing compels a coach to do this. Multi-year contracts protect their salaries. If an employer becomes unsatisfied with a coach’s performance, the school could fire the coach and pay the buyout.

Florida State, especially, backed itself into a corner. The Seminoles would have owed Norvell a buyout topping $63 million after this season, making a coaching change cost prohibitive. Gundy’s buyout topped $25 million.

Either could have dug in his heels. Instead, they took a personal financial hit that favors their employer. Gundy and Norvell proved themselves winners before each experienced a career-worst season this year. Their acceptance of a pay hit allows each school to recoup funds that might improve the program, without triggering a leadership change that could further set back the program.

“Many coaches would rather get paid less and have money to pay players than lose their jobs because of a lack of talent,” sports attorney Mit Winter wrote on X (formerly known as Twitter) in response to Norvell’s announcement.

Not every coach coming off a bad season would agree to this, but, to Winter’s point, Gundy and Norvell are hardly the only ones who would prefer job retention at a reduced salary while reloading at another shot at winning, rather than welcome a severance check and a vacation to Buyout Beach.

In the long-term, perhaps more coaches’ salaries will be reduced and paired with additional performance bonuses for successful seasons, or buyouts could be curtailed to contain costs for firing a losing coach. However, applying more financial caution toward coaching contracts could hurt a school’s hiring or retention efforts.

At the very least, schools should show more caution before awarding senseless raises. Oklahoma gave Brent Venables a hefty raise and an extension before this season, even though Venables did not present as a flight risk after he’d gone 16-10 through two seasons. The Sooners went 6-6 this year, making the raise look especially foolish.

Just last year, Kentucky’s Mark Stoops grumbled that Wildcats fans needed to ‘pony up’ more cash for athletes if they desired a better team. Stoops’ idea to throw more money at the problem holds merit, but he overlooked himself as potential source of funding.

As the pay-for-play revolution wades into waist-deep waters, losing comes at a literal cost for coaches.

Blake Toppmeyer is the USA TODAY Network’s national college football columnist. Email him at BToppmeyer@gannett.com and follow him on X @btoppmeyer. Subscribe to read all of his columns.